Long Meg and Her Daughters (Background: Little Salkeld)

The third largest stone circle in England (after Avebury and Stanton Drew) and the 6th largest in Britain, Ireland, and Brittany) lies just to the north of the small village of Little Salkeld, in the civil parish of Hunsonby, and some 5½ miles NE of Penrith, Westmorland and Furness.

This hauntingly beautiful circle with diameters of 110m east/west by 93 m north/south amounting to 8,011m (0.8ha). The ‘daughters’ of the circle of stones (more of the number later) are local glacial erratics – mica schists from Scotland and Borrowdale volcanics and quartz porphyries from the Lake District; weighing from four up to 30 tons in weight. The menhir, Meg herself, (NY571373) however is of Triassic sandstone, probably brought from the banks of the R. Eden some 1½ miles away or from the Lazonby Fells across the river. She is an impressive 3.8m high with a shallow dished top; estimated to weigh 9 tons and standing about 40 yards southwest of the circle. The circle may be one of Britain’s oldest erected in the years before 3000BC so earlier or possibly contemporaneous with Stonehenge.

The purpose of the circle is, like others, open to speculation and debate, but one has only to stand on the site, with its magnificent raised views of the surrounding land, to see that it would certainly have provided a guiding landmark for travellers; perhaps those making their way to the Langdales to acquire the valuable handaxes. It was almost certainly a centre for local observance of feasts and ceremonies. An interesting case has been made to suggest that these ceremonies would/could have included the Neolithic/Bronze Age festivals of Beltane (a May Day festival), Lughnassad (beginning of the harvest season), Samhain (around the 1st November) and Imbolc (around the 1st February and the beginning of winter and later St Brigid’s/Bridget’s Day). As the picture below shows it was also aligned so that the shadow of Long Meg casts along the centre of the circle at the Winter Solstice.

(Photograph – display board at the site)

Dr. Hugh Todd (1657-1728) put forward the ‘interesting’ speculation that ‘following the king choosing customs of the Danes the Long Meg Circle was the site of the election of Saxon or Danish kings …. for Cumberland’. Stone circles often attract the belief that somehow they were the centres for druids and their practices. In this case the shallow dish on the top of Long Meg was thought to be ‘intended for a place of sacrifice and oblation’. One can only suggest that at a height of 12ft this is a long way up to make an oblation!

The name ‘Long Meg and her daughters’ is intriguing. Most commentators use ‘daughters’ but Celia Fiennes referred to ‘Great Mag and her sisters’. The OED defines ‘Meg’ as a dialect expression ‘to indicate a hoyden, a coarse woman’ and may be of medieval origin and where it is teamed with ‘Long’ to describe any long or slender object as with the gun ‘Mons Meg’ which was acquired by James II of Scotland in 1149 and is 4m long. The term was also ‘applied to persons very tall especially if they have Hop-pole-heighth wanting breadth proportionable thereunto’ (Thomas Fuller, History of the Worthies of Britain (1662)). The Long Meg of the circle is long and not over-fleshed.

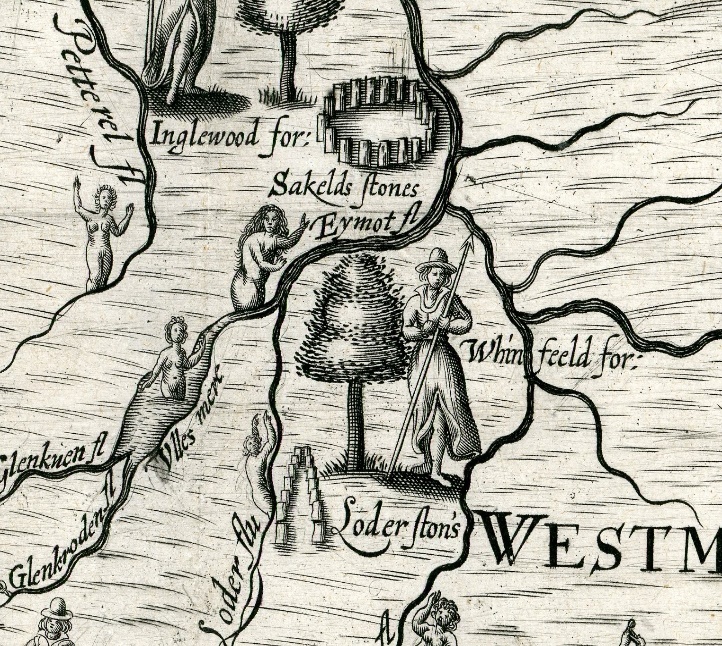

There are other 17th century references which attest to knowledge of, and interest in, the circle. Below is a section of the Polyolbion map of 1622 which shows the ‘Sakelds Stones’

(Illustration - Michael Drayton, Polyolbion: Westmerland and Cumberland, the Thirtieth Song, (1622), courtesy of Dr. William D Shannon)

In 1600 an Appleby schoolmaster, Reginald Bainbridge, told William Camden of ‘certaine monuments or pyramids of stone commonly called meg with her daughters …. They are huge great stones’. If the map and the description are accurate for the time, some of the stones have suffered damage over the centuries. One tradition has it that the number of stones (as with Stonehenge) are uncountable and numbers ranging from 57 to 200 have been recorded. This tradition is part of the one of the tales given as to who and what Long Meg and her daughters were. The story is that they were a coven of witches whose sabbat was interrupted by a magician, Michael Scott, who turned ‘the gaggle of unholy hags’ to stone. Anyone who achieves an exact count of the number of stones will re-activate the coven and suffer consequent damage. A slight variant states that the count must be the same clockwise and anticlockwise. The number now established is 68 (without any serious injury to the counter!). This story may allow a dating of the naming of the stones to around the later 15th and following 16th centuries when the fear of witchcraft was very much a part of life and the stones would be believed to be the ossified bodies of sinners. Other stories are that they were young girls turned to stone for dancing on the Sabbath, and that if a piece is broken off Long Meg the stone will bleed. Celia Fiennes noted the tradition that the ‘sisters’ encouraged ‘Great Meg’ to ‘unlawfull love (probably sex before marriage) and like her were turned to stone for their sins. To end these traditions is the story that at the end of the 18th century Lt.Col. Samuel Lacy of Salkeld Hall ordered his work force to destroy and remove the stones by blasting but a thunder and lightning storm of such violence got up that his work force fled the vengeance of the stones not to return and the stones remain.

Text by Lorna M. Mullett

References:

H.A.W. Burl, ‘The stone circle of Long Meg and Her Daughters, Little Salkeld’, CWAAS, Trans. Vol. XCIV (1994) pp. 1-13

Steven Hood, ‘ Cumbrian Stone Circles, the calendar and the issue of the Druids’, CWAAS, Trans. 3rd series, Vol IV (2004), pp. 1-25

Nicolson & Burn, The History & Antiquities of the Counties of Westmorland and Cumberland, re-published (Wakefield: EP Publishing, 1976) p.448

Ed. Christopher Morris, The Illustrated Journeys of Celia Fiennes c. 1682 – 1712, (London: Macdonald, 1984) p.171